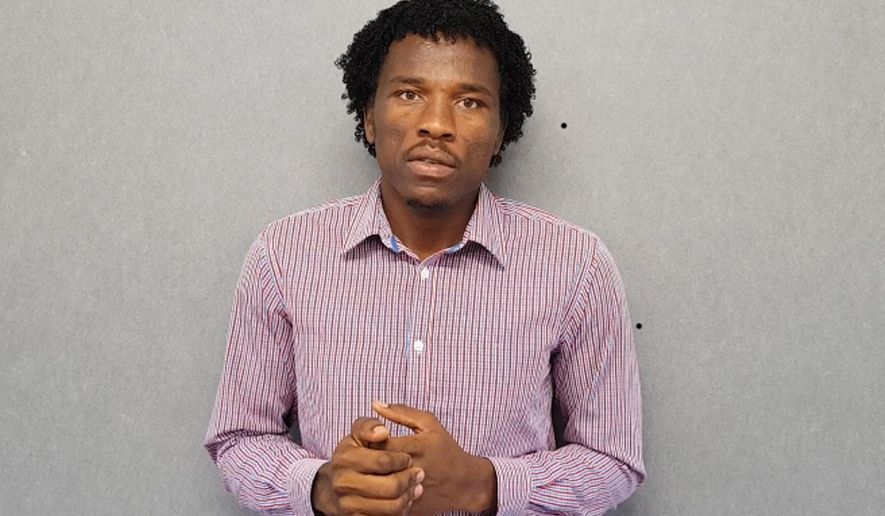

CANBERRA, Australia (AP) - When Aziz Abdul[1] reached Australia[2]’s Christmas Island aboard a smuggler’s boat, he had no idea that weeks earlier in 2013, his fate as a refugee from Sudan seeking a new life in a new world had been sealed.

Australia[3] drew a line in the sand on July 19, 2013, to stem a rising tide of asylum seekers brought by people smugglers on long and treacherous ocean voyages. No refugees who attempted to reach its shores by boat from that date forward would ever be allowed to make Australia[4] their home.

Five years later, the polarizing policy - both lauded as a template for other countries and condemned as a cruel abrogation of Australia[5]’s international obligations - appears to have succeeded as a deterrent. The rickety fishing boats that were arriving from Indonesian ports at a rate of more than one a day have virtually stopped.

But the question of what will become of the hundreds of asylum seekers banished by Australia[6] to sweltering immigration camps in the poor Pacific island nations of Papua New Guinea[7] and Nauru[8] has become more pressing.

“The simplest way for me to describe it is it’s just like hell,” Abdul[9], 25, told The Associated Press by phone from an immigration hostel in a Papua New Guinea[10] village. He now hopes to be chosen among the 1,250 refugees barred by Australia[11] but who President Donald Trump has reluctantly agreed to accept as part of a deal struck between the Australian government and former President Barack Obama’s administration.

“You send people to a place and you want those people to either die or go back to where they came from even if that place is very, very dangerous,” Abdul[12] said. There was a growing sense of hopeless and fear of hostile villagers among the asylum seekers, some of whom no longer speak because of their despair, he said.rmc

Daniel Webb, director of Australia’s Human Rights Law Center, told the U.N. Human Rights Council last month that Nauru[13]’s refugee population included 134 children, 40 of whom had been born there. The number had dropped to 124 by this week, with some children sent to Australia[14] for medical treatment and others to the United States for resettlement.

“With every anniversary, with every birthday and with every death, the sense of hopelessness and sheer exhaustion in these island prisons rises,” Webb said this week. “Our government can’t just imprison them forever.”

Australia[15] offers to pay thousands of dollars to asylum seekers who agree to go home, and many have taken up the offer over the past five years rather than languish any longer in their island limbos. Australia[16] also struck...